TEXT Mark Mann

PHOTOS Daphné Caron

ILLUSTRATIONS David Beauchemin

Story 01

Fish n’ Fraud

Almost half the time the fish you eat isn’t the one you ordered. But what if that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing?

___________

The device was hidden in my backpack when I entered the restaurant. I set my bag on the counter and ordered a meal to go, to avoid suspicion. “I’ll have the fish and chips, please.” Then I took a breath and popped the question: “Where does your cod come from?”

A few weeks before, I had learned about an opportunity to become a “seafood sleuth,” by way of Oceana Canada’s efforts to report on seafood mislabelling in large Canadian cities. The ocean conservation charity was distributing DNA testing kits across the country and sending undercover citizen-scientists to their local restaurants, grocery stores, and fishmongers to collect samples.

Hence the covert tactics at my local fish ’n’ chips joint. The device in my bag was actually a vial containing a clear solution and a pair of blue plastic tweezers. Once outside with my takeout, I hunched over the fried fish, surreptitiously pinched a small, flaky morsel with my tweezers, and quickly slipped it into the vial. I screwed the cap on and gave it a few shakes before depositing it in my bag again. The directions that came with the genetic testing kit also asked us to check the server’s knowledge of the fish’s origins. To this question, the server replied with a laugh, “I have no idea.”

Honestly, can you blame her? Most of us have no idea where the seafood we eat comes from, and few of us ever even bother asking. As far as the average seafood consumer is concerned, the ocean is a giant black box that just happens to cover nearly three-quarters of the earth’s surface. An unbelievable abundance of life resides within its chilly shadows, and most of it remains unknown: an estimated 91 per cent of ocean species have yet to be identified. But almost none of that diversity is reflected in the seafood marketplace, especially in North America. Most of the seafood we eat is either shrimp or canned tuna. Going down the list of popular choices, you get salmon, crab, and pollock, usually in the form of breaded, frozen fish sticks. Even the more complex recipes we love — spicy tuna rolls, shrimp tacos — invariably use the same go-to species we’ve been conditioned to rely on for pescetarian protein for decades.

The bland predictability of our culinary choices isn’t as benign as it seems, however, for our conservative habits have a punishing effect on the rest of the ocean as well. When we latch on to the same handful of fish names that we recognize and insist on eating exclusively, we help to create vast monocultures that drive fish populations to collapse. Today, 80 per cent of the world’s fish stocks are considered to be fully exploited or overexploited. Meanwhile, an invasive species like Asian carp, which has spread throughout North American freshwater systems and overwhelmed many native fish populations, is woefully underexploited, despite its clean, sweet taste. There are many factors that have led to overfishing: poor management, bigger boats equipped with massive nets, and improved technology for targeting fish, like advanced radar and sonar. But when we fixate on the most popular and familiar species, and ignore the equally tasty if less-celebrated species that swim in our waters, only we are to blame for helping to obliterate their populations. Consider the bluefin tuna, driven nearly to the point of extinction because it is considered such a delicacy in sushi restaurants.

Fish tale

But here’s the thing — the seafood industry has a secret. It turns out that half the time, we don’t even know if what we’re eating isn’t what we ordered. Hence the DNA tests.

The Oceana report titled “Seafood fraud and mislabelling across Canada” found that, of 400 seafood samples tested by citizen-sleuths like me, 44 per cent were mislabelled. (Craving snapper? Good luck; 100 per cent of it was mislabeled.) And it’s much much worse in restaurants.

Seafood fraud is such a big problem in part because global supply chains are exceedingly complex. In the U.S., 84 per cent of seafood is imported, and it often travels along an arcane network of international pathways on its journey from boat to plate. Globalized seafood supply chains possess several characteristics that make them difficult to manage: from the start, they are unpredictable, as fishers don’t know exactly what or how much they will catch on any given day; seafood is highly perishable, which puts immense pressure on fishers and sellers to move their product as rapidly as possible; the margins for fishers are paper-thin, compelling everyone along the chain to cut corners and focus on quantity; seafood is frequently disassembled when it is processed, making it even harder to identify; and tracking poses enormous challenges — it’s hard to barcode an individual fish, after all.

As seafood has grown more popular in the last decade, the price has likewise risen by 27 per cent in the U.S.. Seafood is now the largest globally traded commodity by value in the world, according to a report by The Nature Conservancy. This enormous financial opportunity creates further economic incentives for deception in markets. The Oceana Canada report found frequent cases of cheap fish being sold as more expensive species, such as:

“It’s all economics. You seldom pay for a Honda and get a Porsche; it’s nearly always the reverse,” says Robert Clark, a chef and fishmonger who runs a sustainable seafood shop in Vancouver called The Fish Counter. He became acutely aware of the issue when Chilean sea bass arrived in North American markets. “The fillets would be three feet long and huge — the most beautiful whitefish I’d ever had a chance to work with,” he says. But over time, the fillets got smaller and greyer, and Clark realized he wasn’t getting the same fish anymore. That put him over the edge. Tired of the fraud and uncertainty, he decided to buy exclusively from local fishers. “When you’re importing seafood, you don’t know how many hands it touched before it got to your border,” he says.

A fish by any other name

Seafood fraud raises obvious concerns about traceability and the supply chain, but there’s a potential upside. The pervasiveness of mislabelling suggests that our taste in seafood is more expansive than we realize. After all, the ruse works. If we were really that picky, we wouldn’t be so easily duped.

So do we eat with our brains more than our mouths? Dr. Kathryn Medler, a taste physiologist at the University at Buffalo, studies taste in its purest biological sense, as the detection of compounds — bitter, sweet, salty, sour, and umami — by cells in the oral cavity. Everything that happens in our mouths is objective and measurable, she told me, but when the taste system sends that information to the brain, it gets combined with information from the other senses to form the complex and elusive construct known as flavour. For example, smell plays a critical role in determining flavour: when we chew, we release gas molecules in our food that travel up to the nasal cavity and bind to olfactory receptors in distinct and intricate patterns.

But as keen as our taste and smell systems are, they can’t quite compete with our eyes. Our perception is dramatically influenced by labels and other visual elements, says Dr. Joey Hoegg, a researcher in consumer behaviour at the University of British Columbia. “We actually aren’t particularly good at distinguishing different tastes without the assistance of names and visuals,” she told me. “If those labels and visuals create a hypothesis in our mind about how something will taste, the actual taste would have to be substantially different for us to even realize we were not eating what we thought we were.”

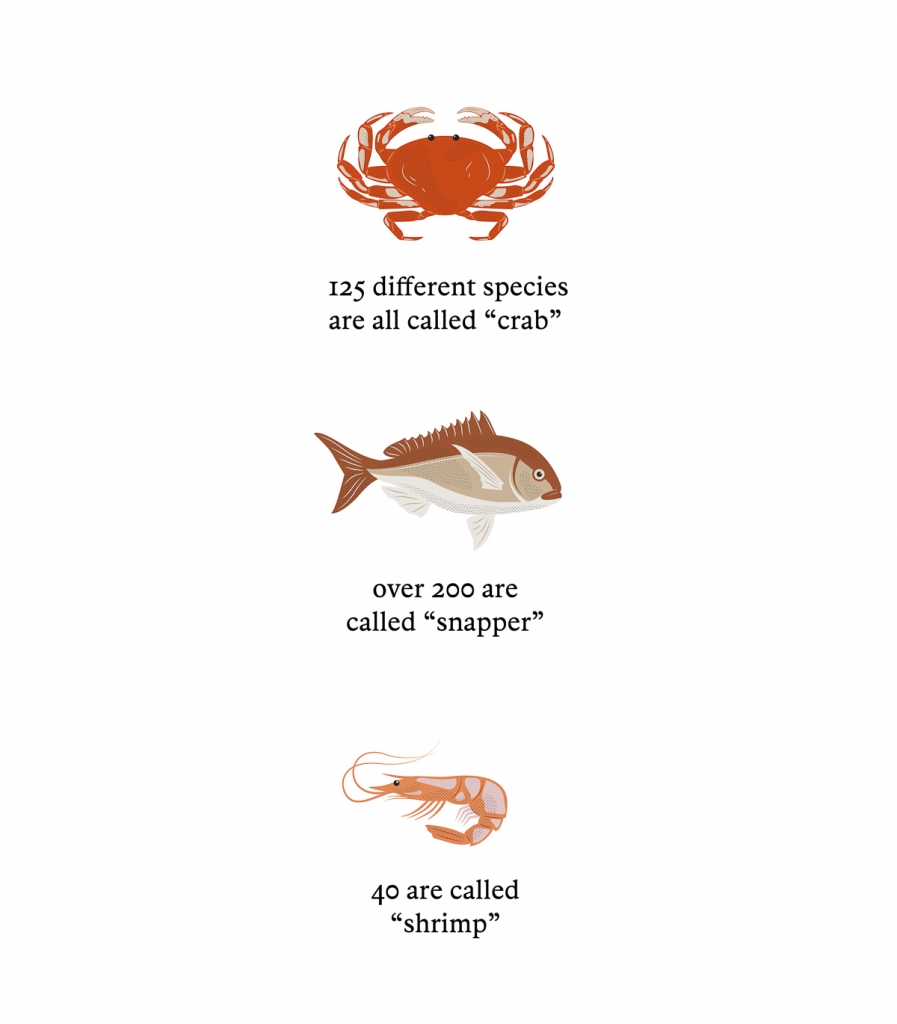

Most people would be happy (and blissfully unaware) eating a larger variety of different fish, as long as it has a familiar name, Hoegg says. And so the seafood industry has happily furnished consumers with a manageable set of recognizable market names to help us make sense of our seafood choices. Yet, even if the fish is labelled correctly, technically speaking, it might not be what we think it is, because the market names we use for fish are too reductive, says Dr. Robert Hanner, a research scientist who helped Oceana interpret the genetic testing data. For example, the words “sole” or “anchovy” are catch-all terms for a variety of fish that have simply been grouped together for convenience. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency allows the lumping of many different species under one common name, according to a report by SeaChoice:

From a meat-eater’s perspective, it would be a bit like going to the butcher’s and finding only two options: four-legs and wings. Fuzzy terminology might simplify our experience of shopping for fish, but it can also lead to outright fraud and enable the laundering of illegal, unregulated, and unreported seafood harvest, says Hanner. He theorizes that when one fish is harvested to the brink of collapse, the industry picks a similar fish that isn’t yet depleted and asks if they can call it the same thing. And the answer that comes back from regulating bodies is resoundingly: “Yes.”

Hanner recommends switching to the model adopted by the European Union in 2017, which requires the Latin name of the species to be displayed with the fish, as well as the region of harvest and the catch method. This helps prevent not only overt seafood fraud, but also the ambiguous naming conventions that can allow the industry to get away with destructive fishing practices. Without scientific identification, consumers are left in the dark about our seafood:

“We don’t know what it is. We don’t know where it comes from. We don’t know how it’s harvested. We really don’t know much more about our seafood than what we would scoring street drugs off the corner,” says Hanner.

But seeing the scientific nomenclature also brings us face-to-face with the ocean’s daunting complexity. Is that the dose of reality we need to confront our habitual conservatism when it comes to eating fish?

Be your own culinary hero

Anyone who wants to take charge of their flavour preferences has a steep hill to climb. For starters, there are genetic, environmental, and personality factors to overcome. We all share the same biological taste system, no matter where we come from, but the details of our taste and smell receptors do vary: more or less of one type of receptor will alter our sensitivity to different compounds in food. You might have a variety-seeking personality, but it won’t help much if your mouth is hyperattuned to bitterness, says Dr. Helene Hopfer, a professor of food science at Penn State University.

Environmental influences also direct our preferences. For example, where you were born will largely determine whether or not you like pickled herring. Indeed, some of our predilections are shaped before we’re born, by way of aroma compounds transferred via amniotic fluid in the womb. “You are what your mother ate,” says Hopfer.

Class plays a role too. “There’s a big divide between people who can afford (both mentally and financially) to think about aspects of sustainability and ethics when it comes to what they eat,” says Hopfer.

Finally, evolution, too, reinforces our habitual culinary conservatism. Reticence to try new foods is a trait that would have been favoured by natural selection, as this behaviour protected us from harm, says Medler. She proposes a thought experiment: if aliens beamed a potentially edible substance to earth, would you pop it in your mouth? Probably not, “because we have evolved not to eat things that are completely unknown to us.” For most of us, the ocean is as alien as it gets, so it’s no wonder we hesitate to experiment with strange new fish.

But there is a way around these social and biological barriers, says Hopfer: although we won’t eat something we’ve never seen before on our own, we will if it looks like something we do like to eat, and if others lead the way. This fact partly explains why culinary trends in general have been getting increasingly adventurous since the 1950s, says Dr. Nathalie Cooke, who researches cookery literature at McGill University in Montréal. Globalization has contributed to the decimation of fish stocks by enabling planetary mega-trends, but the same forces that have shrunk the planet (i.e., cheap plane travel, the internet) can help us overcome our rigid eating habits. The more contact we have with other culinary cultures, the more we acquire openness in trying new things.

For those wary of getting caught up in global food fads, however, there’s another way to expand your seafood horizons in a more sustainable direction: head down to your local fishmonger and ask for help finding good local choices. They’ll also show you what to do when you take the fish home. “We teach people how to cook the fish, because many don’t know how,” says Bernard Cormier, a manager at Poissonnerie Shamrock near my house. People boil or bake fish five times longer than necessary, he says: “They complicate life. Fish is the easiest thing to cook.”

An Acadian from New Brunswick, Cormier has worked in the business for 42 years, and he’s seen some changes. The biggest change is that now everyone wants fillets. “It’s not like it was. When I started, they used to buy the whole fish and take care of it themselves,” he says. “Now they don’t want to clean the fish themselves, They want us to clean them. ”But even if fish-literacy has fallen somewhat, people have always needed help with fish and seafood, Cormier says. He’ll sometimes push customers to try a species like monkfish, which is ugly as hell but tastes wonderful. “You have to get personal with the customers. You have to take them by the hand and explain things.” Robert Clark, who’s been cooking and selling fish for four decades, agrees. “When the needle is moved, it’s always through persuasion,” he says.

Mild white fish like halibut and sole sell quickly and easily, says Clark, but when those fish are out of season, customers need to be convinced to step outside their comfort zones.

People do actually change, though not easily. When Robert Clarke started as a chef in Toronto, even salmon was considered undesirable. It took a massive marketing effort by the salmon industry to convince people to eat the healthy pink fish, he says. Clark would like to see something similar happen for seafood that’s lower on the food chain: herring, anchovies, sardines. “The lower it is, the healthier it is, and better for the planet.” These small, oily fish are also cheaper and more flavourful. But people need to be convinced. How? “Make them taste good,” says Clark.

Hearing fishmongers like Clark and Cormier come to bat for the lesser-loved species, it strikes me that the solution to our bland timidity around seafood starts right here at the fish counter, with honest questions being asked and a nice bit of conversation at the store. Traceability and scientific labelling are critical, but the real foundation for sustainable seafood comes from a mix of curiosity and guts. If you’re feeling uncertain, trust your taste buds: they’re braver than you think.

______________________

Mark Mann is an independent journalist and editor who specializes in literary longform storytelling. He covers topics related to health, technology, culture, and the environment, and his feature stories have appeared in Toronto Life, the Walrus, the Toronto Star, and Maisonneuve, among others.

Never Miss Another Issue

Two issues per year

25% OFF previous issues

Free Shipping in Canada